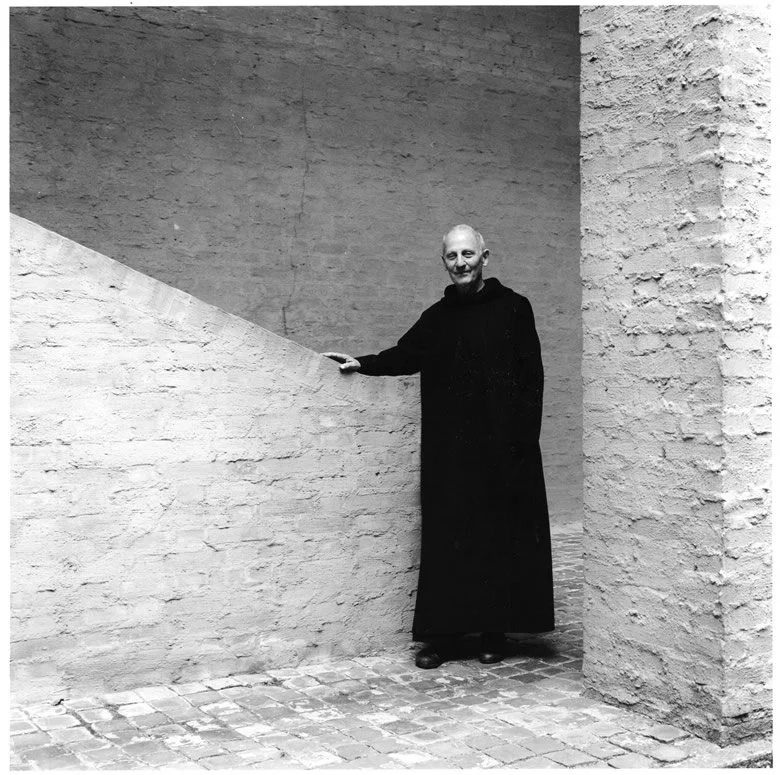

Dom Hans van der Laan

(1904 - 1999)

Born in the Dutch town of Leiden in 1904, Dom Hans van der Laan - monk, architect and leading figure of the Bossche School - occupies a unique position in the world of architecture.

The son of an architect, van der Laan intended to follow in his father’s footsteps by studying architectural engineering in Delft (1923-1926) however, he soon abandoned his studies for St. Paul’s Abbey, Oosterhout to become a monk. Within the confines of the monastery he once again turned to architecture. In the freedom he experienced there, uninfluenced by his surroundings and distanced from discussions in the world of architecture, he was able to give shape to a new vision of architecture.

Approached from a philosophical, theological and technological perspective, his architecture examines the primeval origin of architectural principles and the fundamental essence of the form.

Van der Laan believed architecture should create spaces that are finely attuned to the experiential aspects of being human. Spaces that not only offer protection from the outside, but which offer tranquility and order - qualities van der Laan considered basic human needs. On both a theoretical and practical level, he sought to give significance and importance to simplicity. A voice to silence, a form to the void.

How he achieved this derives from a fundamental relationship - that of architecture and nature. In nature, and through the extremely methodical observation of its phenomena, van der Laan sought rhythms and rules that he later incorporated into design and construction. Architecture, he constantly emphasized, did not consist of creating something out of nothing but rather of recognizing and transforming that which already existed in the natural world.

“The forms of the objects that we make as humans are always modifications of natural forms because we can’t conjure these objects into existence out of nothing; we alway make something out of something and in the final instance, it is something that exists in nature” (Liturgie en Architecture, Ghent 1978)

Van der Laan didn’t perceive the golden ratio as being directly relevant to architecture and instead began to develop the principles for his own proportion theory. This would later become the ‘Plastic Number’, a theory which he spent decades formulating and teaching.

Based on the universal laws of human perception, the plastic number is, in essence, a system for ordering and measuring the proportions found in nature, as well as in many architectural movements in the classical antiquity of various cultures. Through this ratio, a certain proportion is maintained throughout any scale, creating harmonious relationships between all objects in the space.

Photo credit: Tim van de Velde

Challenging to summarize given its flexibility, the basic principle of the plastic number as it relates to architecture is that the thickness of the wall within a space represents the smallest measurement. The space is then not only determined by the form of the wall - its height, width and depth - but also by the proportions between the depth and distance of each individual wall.

If Dom Hans van der Laan’s innovative work is characterized by an all embracing simplicity, numbers are the only decoration present. These numbers govern his formal choices and establish a relationship between the parts but, once used, disappear without a trace, leaving only the invisible harmony that permeates.

Music is a fundamental component of the Benedictine monastic practice and one on which van der Laan lectured in addition to architecture. He was strongly attracted to it because of its numerical basis and how, with a limited system of elements and a great variety of relationships, it could transform ordinary sounds into symphonies. If, for van der Laan, architecture and design could reveal the immanent presence of beauty in the everyday, masterly use of compositional skill and formal simplicity were the instruments he used to reveal this. For van der Laan, architecture creates the backdrop for the rhythmic performance of daily rites, like sound boxes that reflect gestures, echo sounds and - above all - create silence.

Image Credit: Jeroen Verrecht

In the essential quality of van der Laan’s work, his treatment of exterior spaces, and the simplicity of his architecture and design, one can perceive an echo of Zen practices. This stems from a common conceptual and formal background focusing on spirituality and nature. The careful arrangement of trees, lawns and bushes so that they and the architecture form a single representation - is reminiscent of the precise control of nature that completes the design of Shinto monasteries. The relationship between interior and exterior, one of the most common themes of Japanese architecture, is also one of the cornerstones of Benedictine teaching in the field of architecture. The simplicity of the tea houses and pavilions of Katsura is similar to that of the Cistercian monasteries, which makes sense given an analogous desire guides the hand of their architects: to react against the excess of the world in search of a new architectonic truth. Architecture replaces decoration in places destined for meditation and faith.

Though he consciously avoided discussions within the world of architecture, it has been said that van der Laan combined the Rule of Saint Benedict with the spirit of De Stijl. Gerrit Rietveld is known to have been a great admirer of Van der Laan’s work. He in fact visited Delft to give a lecture in 1958 and later invited van der Laan to visit his home, where the pair discussed architecture and design at length.

Furniture

While DHVDL’s legacy is certainly embedded in his buildings, he believed in the totality of design in the spaces he created and attributed just as much importance to the design of individual objects and furniture. He had a hand in every single detail present in his buildings: furniture, linens, bible covers, plaques, tiles, new families of fonts for stone encryptions, even monastic robes.

As in his architecture, the process of extreme simplification and adaptation to the rules of the plastic number led to the production of furniture and objects that hover between the recognizable and the abstract. Produced by assembling planks of wood, mainly pine, pieces are ‘measured’ by clearly visible lines of nails - three for each plank. On their distinct, subdued color palette, van der Laan worked with the Dutch artist Wim van Hooff (1918 - 2002), one of the leading and most outspoken color consultants of the second half of the twentieth century. A painter, van Hooff had developed his own vision on the use of color and balance in architecture, resulting in the subdued color palette that characterizes the architecture of the Bossche School.

"I therefore rely on a willingness to sacrifice lower concerns for higher ones, such as must so frequently be the case in spiritual life. And that higher concern is above all the great unity of furniture and space, and the peace that this communicates to the mind and spirit. We constantly considered this kind of furniture in relation to the space in which it stands and which it completes, and in such a way that we consistently matched its colours to those of the space. Mr van Hooff coloured this furniture, as it were, using the shadow tones of the walls, as was done for the doors in your house.” (VDL, 9 letters)

Under van der Laan’s supervision, a series of furniture was made by the Dutch company, Gorisse, in the late 1970’s - early 1980’s for the purposes of an exhibition at St Benedictusberg Abbey in Vaals in 1982. The pieces produced by Gorisse differ from VDL’s typical plank construction in that they have completely flat, paneled exteriors.

The Bossche School and van der Laan’s Disciples

Dom Hans van der Laan was not only a theorist, an architect and a designer, he was also a widely influential teacher. A course in his innovative architecture commenced in Den Bosch in 1946 and continued through 1973. This course, which van der Laan lead alongside his brother, Nico van der Laan, also an architect, formed the basis of the Bossche School, a traditionalist movement in Dutch architecture based on numerical relationships and with simplicity as a guiding principle.

Van der Laan built relatively little himself. However, throughout his lifelong examination and exploration of architecture, he increasingly found support and disciples. The architecture firm of his brother, Nico, and his partners, W. Hansen and H. Van Hal, played a pioneering role in putting into practice van der Laan’s ideas. Between 1945 - 65, including the post-war reconstruction period, his influence was particularly immense and he was often consulted by other architects not only in connection with the refurbishment of churches but also regarding more worldly buildings. Although he built remarkably little himself, in 1989 he was awarded the Limburg Architecture Prize for his 1986 design of the library wing with staircase and gallery for the Abbey of St Benedictusberg in Vaals, and for all his work in the service of architecture, in the areas of education as well as construction.

Photo credit: Jeroen Verrecht

Jan de Jong (1917 - 2001), was an early participant in the course at Den Bosch and quickly recognized by van der Laan as his most brilliant pupil. De Jong would become one of his most important disciples, working extremely closely with van der Laan until his death in 1991. During the reconstruction period following WWII, van der Laan and de Jong collaborated on several architectural projects, including all interior furniture. They created an outstanding body of work, defining the style of the Bossche School. de Jong was able to translate many of van der Laan’s idealized concepts and ideas into pioneering buildings and spaces. They in fact worked in such close collaboration that it is difficult to discern the individual level of input into the furniture they designed.

Dom Hans van der Laan: A Visual Silence opens Friday, September 8th, 2023 and will remain on view through October 21st, 2023.

FORM ATELIER

51 White Street, New York, NY 10013

Tuesday - Saturday, 11am - 4pm

Additional information on Dom Hans van der Laan and an in-depth look at his theory of the ‘Plastic Number’ can be found here. The website and its content are developed by Caroline Voet, Faculty of Architecture, KU Leuven, in collaboration with the Van der Laan Archives and the Van der Laan Foundation.